We’ve all been there: a scraped knee, a paper cut, or an unfortunate encounter with a kitchen knife. A few days later, a crusty, reddish-brown patch forms over the wound. It’s a scab—nature’s biological bandage. But what exactly is it? And why is it so tempting to pick at, even when we know we shouldn’t?

Let’s dive into the fascinating science behind scabs and settle the age-old debate: to pick or not to pick.

What Is a Scab, Really?

At its core, a scab is a protective crust made primarily of fibrin and platelets—components of your blood that spring into action when you get injured.

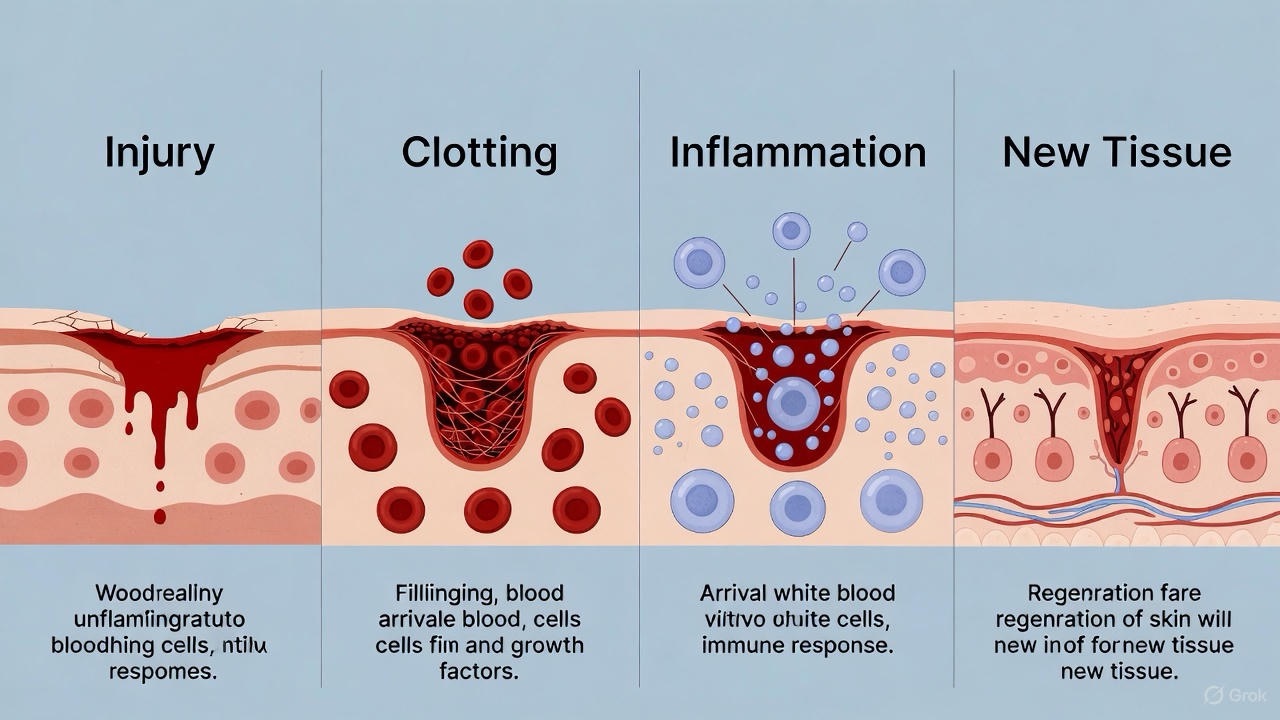

Here’s the step-by-step process:

1. Injury Occurs: Your skin is broken, and blood vessels are damaged.

2. Platelets to the Rescue: These tiny cell fragments rush to the site and clump together to form a plug, reducing blood loss.

3. The Clot Forms: Proteins in your blood, especially fibrin, create a mesh that traps platelets and red blood cells, forming a clot.

4. Drying Out: When exposed to air, the clot dries and hardens into a scab—a natural barrier against bacteria, dirt, and further injury.

Under that crust, your body is hard at work. White blood cells clean the area, fibroblasts rebuild collagen and tissue, and new skin cells multiply from the edges inward.

The Itch Factor

One of the main reasons scabs become so irresistible is that they itch. This itching is a sign of healing—nerve endings are regenerating, and histamines are released as part of the inflammatory process. While it’s a positive signal, it’s also a test of your willpower.

To Pick or Not to Pick?

It might be satisfying, but here’s why you should resist the urge:

The Risks of Picking:

· Infection: Removing the scab re-exposes the wound to bacteria.

· Scarring: Disrupting the healing process can lead to larger, more noticeable scars.

· Delayed Healing: Every time you pick, you restart part of the healing timeline.

· Bleeding: You can cause fresh bleeding and reintroduce clot-forming demands on your body.

The (Small) Case for Careful Removal

Sometimes, a scab might be accidentally lifted or seem ready to come off. If it’s been at least a week, the wound underneath is no longer raw, and the scab lifts easily with no resistance, it’s likely safe. But if there’s pain, moisture, or bleeding, stop immediately—it’s not ready.

How to Support Healthy Healing

1. Keep It Clean: Gently wash with mild soap and water.

2. Moisturize: Petroleum jelly or antibiotic ointment can keep the area moist, which actually speeds healing and reduces scab formation.

3. Cover Up: Use a bandage to protect from dirt and temptation.

4. Don’t Scratch: If it itches, tap around it gently or apply a cold compress.

When to See a Doctor

Most scabs are harmless and fall off on their own within a week or two. Consult a healthcare provider if:

· The area becomes increasingly red, swollen, warm, or painful.

· Pus or foul-smelling discharge appears.

· You notice red streaks spreading from the wound.

· Healing doesn’t progress after two weeks.

The Bottom Line

Scabs are a sign of your body’s incredible ability to repair itself. That crusty patch is a temporary shield, guarding the delicate work happening beneath. While picking might offer momentary satisfaction, it comes at a cost to your skin’s recovery and appearance.

Next time you spot a scab, admire it for what it is—a tiny, biological masterpiece in the art of healing. Let it do its job, and reward yourself with the best outcome: healthy, scar-free skin.

Listen to your body. It’s wiser than your fingertips.

FAQs

1. Why do scabs form?

Scabs form as a natural part of the healing process. When you bleed, platelets and fibrin proteins in your blood create a clot to stop the bleeding. This clot dries and hardens when exposed to air, forming a protective seal over the wound to keep out bacteria and dirt while new skin grows underneath.

2. Why do scabs turn dark brown or black?

The color comes from the red blood cells trapped in the fibrin mesh of the clot. As the red blood cells dry out and break down, their hemoglobin (the iron-rich protein that carries oxygen) oxidizes. This process turns the scab from a bright red to a dark brown, maroon, or even blackish color—similar to how a cut apple turns brown.

3. Is it ever okay to pick a scab?

It’s best to let them fall off naturally. If a scab is very loose at the edges, barely attached, and the skin underneath looks fully healed (pink and smooth, not raw or wet), you can gently remove it. Never force, peel, or scratch one off. Forced removal almost always delays healing and increases scarring.

4. Why do scabs itch so much? Is that a good sign?

Yes, itching is generally a sign of healing! It happens for two main reasons:

· Histamine Release: As part of the inflammatory response, your body releases histamines, which cause itchiness.

· Nerve Regrowth: New nerve endings are being formed and reconnected under the scab, which can trigger itchy sensations.

5. What’s the white/yellow stuff under or around my scab?

A small amount of whitish-yellow fluid (plasma) or a soft yellow crust can be normal—it’s often a mix of dead white blood cells, bacteria (both good and bad), and other cellular debris. However, if you see thick, pus-like discharge, increased redness, swelling, or feel warmth, it could be a sign of infection and you should see a doctor.

6. Do scabs heal faster when covered or left to “air out”?

Modern wound care science says covered (moist) healing is faster. Keeping a scab moist with petroleum jelly and a bandage prevents the wound from drying out completely. This creates an ideal environment for new skin cells to migrate and repair the area, reduces itching and temptation to pick, and often results in less scarring. Letting it dry and scab is the body’s default, but not necessarily optimal.

7. What happens if I accidentally knock my scab off too early?

Don’t panic. Gently clean the area with mild soap and water, apply an antibiotic ointment or petroleum jelly, and cover it with a clean bandage. It will likely form a new, smaller scab as the healing process restarts. Watch for signs of infection.

8. Will picking a scab always cause a scar?

It significantly increases the risk. Picking disrupts the organized rebuilding of tissue, can cause deeper damage, and re-triggers inflammation. This often leads to a larger, thicker, or more discolored scar (like a raised keloid or pitted scar) than if you had left it alone.

9. How long should a scab last?

Typically, a scab forms within a few hours to a day, persists for about 5 to 14 days depending on the wound size and location (areas with more movement, like over a joint, take longer), and then falls off on its own. If a scab lasts for more than two weeks without signs of healing underneath, consult a doctor.

10. What’s the difference between a scab and a scar?

· Scab: A temporary, crusty protective cover made of dried blood and plasma.

· Scar: The permanent result of the healing process. After the scab falls off, the new skin (made of collagen fibers) may look pink, raised, or different in texture. This remodels over months to become a mature scar.

11. Are there ways to minimize scarring after a scab?

Yes, after the wound is fully closed and the scab is gone:

· Sunscreen: New skin is very prone to hyperpigmentation. Protect it with SPF 30+ for at least 6 months.

· Silicone gels/sheets: Proven to help flatten and soften scars.

· Gentle massage: Can help break down tough collagen fibers in raised scars.

· Keep it moisturized: Use fragrance-free creams to maintain skin elasticity.

12. When should I be worried about a scab?

See a healthcare provider if you notice:

· Increasing redness, swelling, warmth, or throbbing pain.

· Pus or a foul smell.

· Red streaks radiating from the wound.

· Fever or chills.

· The wound isn’t getting smaller or continues to bleed.

· The scab is very thick over a large puncture or animal/bite wound (these need professional assessment).