You fall off your bike and scrape your knee. You cut your finger while cooking. Your body’s response is immediate and visible: the area becomes red, warm, swollen, and tender to the touch. For centuries, these signs have been interpreted as the body’s “angry” reaction to injury. But what if we’ve been misunderstanding this critical process? What if redness and swelling aren’t just signs of damage, but the essential first act of repair?

Welcome to the inflammatory stage of healing—the body’s emergency response and cleanup crew rolled into one. This stage, while often uncomfortable, is not only a good sign but a non-negotiable prerequisite for proper healing.

Beyond “Infection”: The Four Cardinal Signs Explained

The classic signs of inflammation—redness (rubor), heat (calor), swelling (tumor), and pain (dolor)—have a specific, purposeful design:

· Redness & Heat: The result of vasodilation. Your body sends a chemical signal (like histamine) to the tiny blood vessels at the injury site, instructing them to widen. This increases blood flow, delivering a surge of oxygen, nutrients, and specialized repair cells to the area. The increased circulation causes the familiar red and warm appearance.

· Swelling: As blood vessels become more permeable, plasma (the fluid part of blood) leaks into the surrounding tissue. This swelling, or edema, has two key jobs: it helps isolate the injury by creating a fluid cushion, and it brings critical proteins and antibodies to the site to fight potential invaders.

· Pain: Triggered by both the injury itself and the pressure from swelling, pain serves a vital protective function. It forces you to protect and rest the injured area, preventing further damage and allowing the repair process to begin undisturbed.

The Cast of Cellular Characters: Your Microscopic First Responders

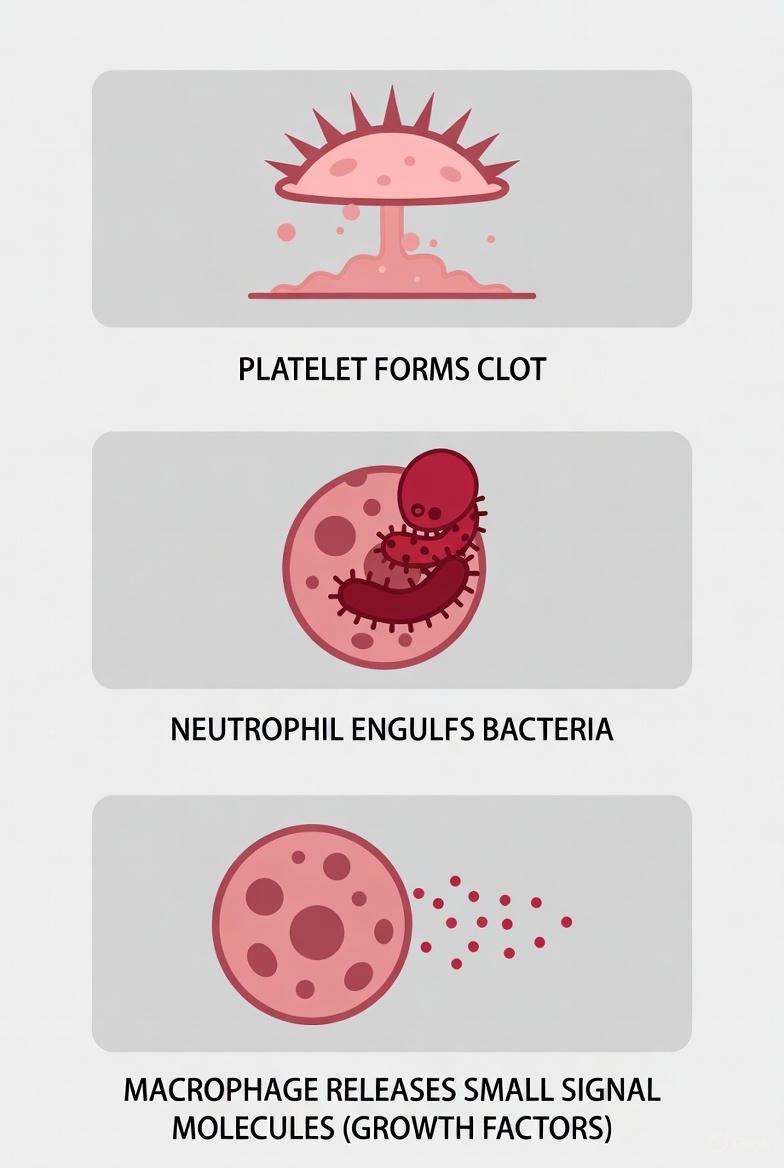

This stage is directed by a perfectly choreographed cellular response:

1. Platelets: The first on the scene. They rush to form a clot, stopping the bleeding and creating a temporary scaffold for what’s to come.

2. Neutrophils: The initial “clean-up” crew. These white blood cells arrive to engulf and destroy any bacteria or foreign debris, using powerful enzymes. They are the short-term defenders.

3. Macrophages: The master regulators. These cells arrive next to finish the cleanup, consuming dead tissue, spent neutrophils, and any remaining pathogens. Crucially, they also release chemical messengers called cytokines and growth factors that signal the next stage of healing to begin. Without macrophages, healing stalls.

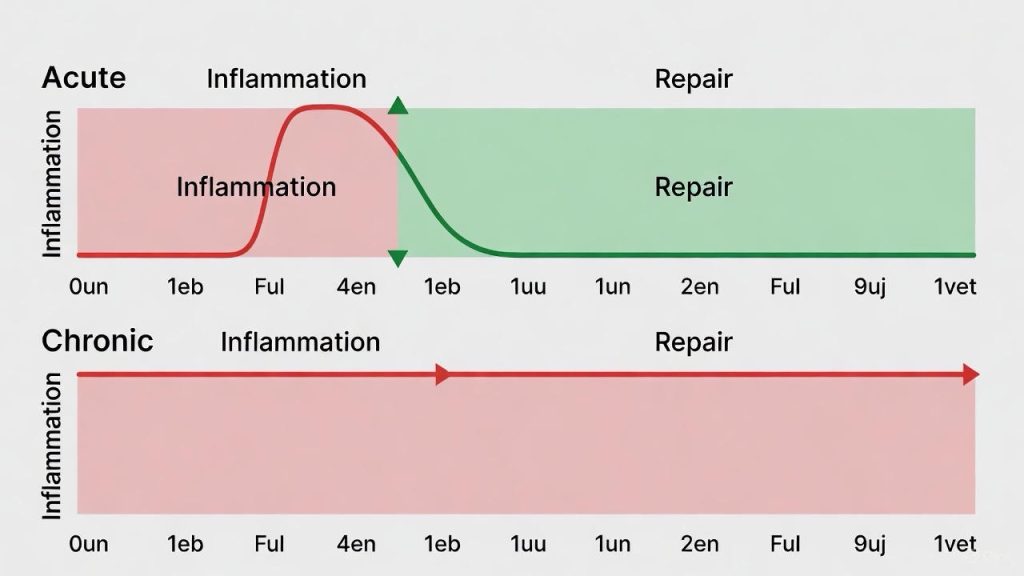

When “Good” Inflammation Goes Bad: Acute vs. Chronic

This is the crucial distinction. The process described above is acute inflammation—a tightly controlled, self-limiting process that lasts from a few hours to several days. It’s purposeful and productive.

The problem arises when this process doesn’t resolve. Chronic inflammation occurs when the inflammatory response persists for weeks, months, or even years. Instead of repairing, it begins to damage healthy tissue. This is what happens in:

· Non-healing chronic wounds (like diabetic ulcers)

· Autoimmune diseases (like rheumatoid arthritis)

· Inflammatory conditions (like tendinosis)

Chronic inflammation represents a stalled healing process, where the body is stuck sounding the alarm without moving on to repair and rebuild.

How to Support (Not Suppress) the Inflammatory Stage

The instinct to immediately ice and take anti-inflammatory medication (like ibuprofen) for every minor injury is being re-examined by sports medicine science. While these methods are excellent for managing severe pain and excessive swelling, they may potentially interfere with the body’s natural signaling process if used too aggressively too soon.

Best practices to support acute, productive inflammation:

1. P.R.I.C.E. (Modified): Protect and Rest the area are paramount. Use Compression and Elevation to manage excessive swelling that causes significant pain or loss of function. The role of Ice is now seen as primarily for pain relief, not to stop inflammation altogether.

2. Nourish Your Body: Provide the raw materials for healing. Focus on anti-inflammatory foods: omega-3s (fatty fish), antioxidants (berries, leafy greens), and proteins. Stay hydrated.

3. Listen to Pain: Pain is information. Respect it. Avoid “working through” sharp, acute pain in a fresh injury.

4. Know When to Intervene: Support doesn’t mean neglect. Clean the wound to prevent infection, which is a harmful external invader that hijacks and prolongs inflammation.

Red Flags: When Redness and Swelling Signal Danger

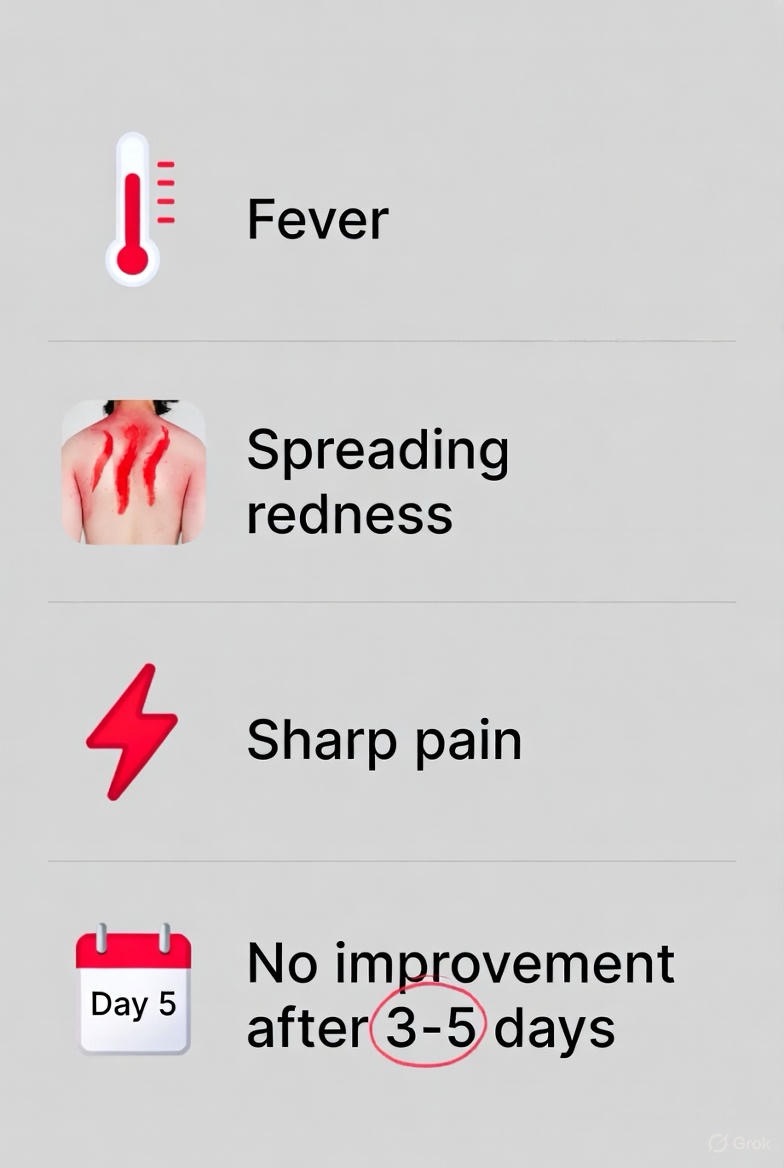

While normal inflammatory signs are localized and begin to improve within a few days, watch for signs that indicate a problem—most commonly infection or excessive inflammation:

· Spreading Redness: Red streaks moving away from the wound.

· Increasing Pain: Pain that worsens significantly after 48 hours.

· Pus or Thick, Foul-Smelling Drainage.

· Systemic Symptoms: Fever, chills, or general malaise.

· Swelling that is severe, continues to increase, or severely limits movement.

These signs require immediate medical attention.

The Bottom Line: Respect the Process

The next time you see redness and swelling around a fresh injury, try to see it for what it is: the visible evidence of a sophisticated biological rescue operation. It is your body marshaling its resources, cleaning the site, and laying the groundwork for rebuilding.

Our goal should not be to completely eliminate this vital stage, but to understand it, support it, and differentiate between productive healing and a process that has gone awry. By working with our body’s innate intelligence, rather than immediately against its signals, we can foster a more optimal environment for true and complete recovery.

FAQs

Q1: If redness and swelling are good, should I avoid icing a new injury?

Answer: This is a modern point of debate. Current sports medicine thinking suggests:

· Ice is excellent for severe pain relief. Use it to manage acute, debilitating pain.

· Avoid over-icing with the sole goal of stopping all inflammation. The inflammatory process delivers essential repair cells. Icing too aggressively or too long may potentially blunt this necessary cellular response.

· Best Practice: Use ice sparingly (10-15 minutes at a time) primarily for pain control in the first 24-48 hours, while prioritizing Protection, Rest, Compression, and Elevation (P.R.I.C.E.) to manage excessive swelling.

Q2: How long should normal “good” inflammation last?

Answer: For a typical acute injury (sprain, minor cut, bruise), the peak inflammatory phase—with the most noticeable redness, heat, and swelling—usually lasts 2-5 days. It should then gradually begin to subside as the body moves into the repair phase. If these signs are increasing after 48-72 hours, it may signal a problem like an infection or overly severe trauma.

Q3: What’s the difference between inflammation from healing and inflammation from infection?

Answer: Key distinctions:

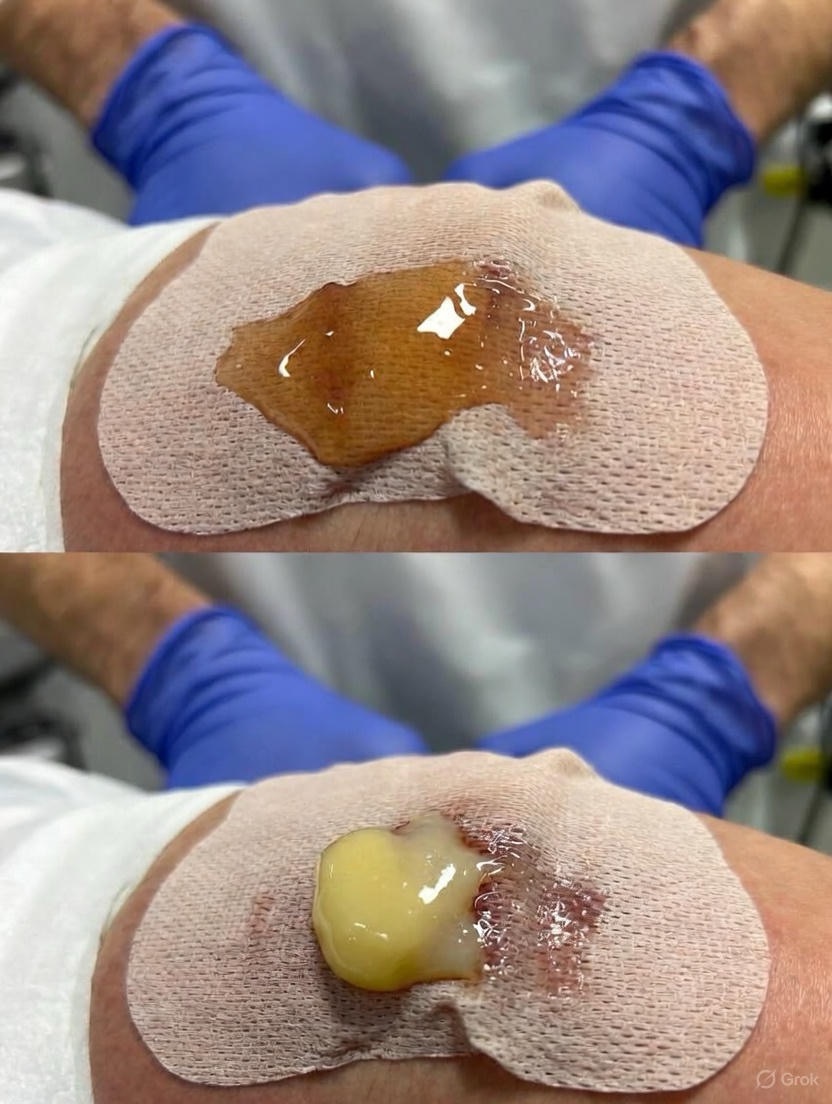

· Healing Inflammation: Localized to the injury site. Redness is stable or improving. Pain is often a steady, dull ache or throbbing. There is minimal drainage, or clear/lightly pink fluid.

· Infectious Inflammation: Redness spreads in streaks. Pain sharply increases. Heat is more pronounced. Drainage is thick, yellow/green pus, often foul-smelling. Accompanied by systemic signs like fever or chills.

Q4: Do anti-inflammatory pills (like ibuprofen) slow down healing?

Answer: The science is nuanced. NSAIDs (e.g., ibuprofen, naproxen) work by inhibiting prostaglandins, chemicals that promote pain and inflammation.

· Short-term use for severe pain is generally considered acceptable and can help you move and rehab.

· Prolonged/high-dose use in the initial healing phase may potentially interfere with the early cellular signaling (like platelet and macrophage activity) that initiates repair, especially for bone and tendon injuries. Consult your doctor for timing and dosage specific to your injury.

Q5: Why does chronic inflammation happen, and why is it bad?

Answer: Chronic inflammation occurs when the “on” switch for inflammation gets stuck. Instead of a short, controlled burst, the inflammatory cells and chemicals linger and begin to attack healthy tissues. This is damaging because:

· It destroys rather than repairs.

· It’s linked to conditions like chronic wounds, arthritis, heart disease, and more.

· It represents a failed transition from the inflammatory stage to the proliferative (repair) stage of healing.

Q6: Can I eat certain foods to help or reduce inflammation?

Answer: Absolutely. Diet significantly influences your inflammatory response.

· Pro-Inflammatory Foods to Limit: Sugary drinks, refined carbs, fried foods, processed meats, and excessive alcohol.

· Anti-Inflammatory Foods to Emphasize: Fatty fish (salmon, mackerel – high in Omega-3s), berries, leafy greens, nuts (walnuts, almonds), olive oil, and tomatoes. Staying hydrated is also crucial.

Q7: What does it mean if my injury isn’t red or swollen?

Answer: A lack of inflammation can also be a concern, indicating poor circulation or impaired immune function. This is common in:

· Diabetes: Neuropathy and vascular disease can blunt the inflammatory response, which is why foot injuries are so dangerous.

· Autoimmune Disorders or Immunosuppressant Medications: The body’s ability to mount an initial response may be impaired.

In these cases, the absence of classic signs does not mean an injury is minor; it requires careful monitoring.

Q8: Is pus a sign of healing or infection?

Answer: Pus is almost always a sign of infection. It’s a thick, whitish-yellow fluid composed of dead white blood cells (neutrophils), bacteria, and tissue debris. While neutrophils are part of the normal inflammatory cleanup, their accumulation into pus indicates they are fighting a significant bacterial invasion. Clear or lightly pink fluid (“serous exudate”) is a normal part of inflammation; pus is not.

Q9: How does swelling actually help healing?

Answer: Swelling (edema) has important functions:

1. Cushioning: The fluid creates a physical barrier to protect the injured area from further impact.

2. Delivery System: The fluid plasma carries antibodies, proteins, and nutrients vital for cleaning and repair to the exact site they’re needed.

3. Immobilization: The stiffness and pressure from swelling encourage you to rest the injured part.

Q10: When should I be concerned about inflammation and see a doctor?

Answer: Seek medical attention if you observe:

· Signs of infection (as above: spreading redness, pus, fever).

· Swelling that is severe, causes numbness, or cuts off circulation (extreme tightness, pale/bluish skin).

· Inability to bear any weight or use the injured limb at all.

· No improvement in pain and swelling after 3-5 days of home care.

· Underlying health conditions (diabetes, vascular disease, immune issues) where any wound needs professional assessment.

Key Takeaway:

Inflammation is not the enemy of healing; it is its essential, powerful first chapter. Your goal is not to eliminate it but to manage its excesses while respecting its purpose. Learn to differentiate between the productive, self-limiting redness and swelling of repair and the destructive, spreading signs of infection or chronic dysfunction. Trust the process, but be a wise and observant partner in your own recovery.