A child takes a tumble off their bike. A young athlete gets a bump on the head during a game. In the whirlwind of childhood, head knocks are common. While many are minor, any blow to the head or body that causes the brain to shake inside the skull can result in a concussion—an invisible but serious injury.

As a parent, coach, or caregiver, knowing how to spot the signs and when to act is not just helpful—it’s critical for a child’s long-term health and recovery. This guide will walk you through what to look for, what to do immediately, and when a trip to the hospital is non-negotiable.

What is a Concussion? The Simple Science

A concussion is a type of traumatic brain injury. It’s not a bruise or a bleed you can see on an X-ray; it’s a disruption in the brain’s normal functioning. Imagine the brain as a soft, delicate computer. A hard jolt can scramble its wiring temporarily. This “scrambling” causes the symptoms we see. Concussions are always serious, and children’s developing brains can be more vulnerable.

What to Look For: The Red Flags (Signs & Symptoms)

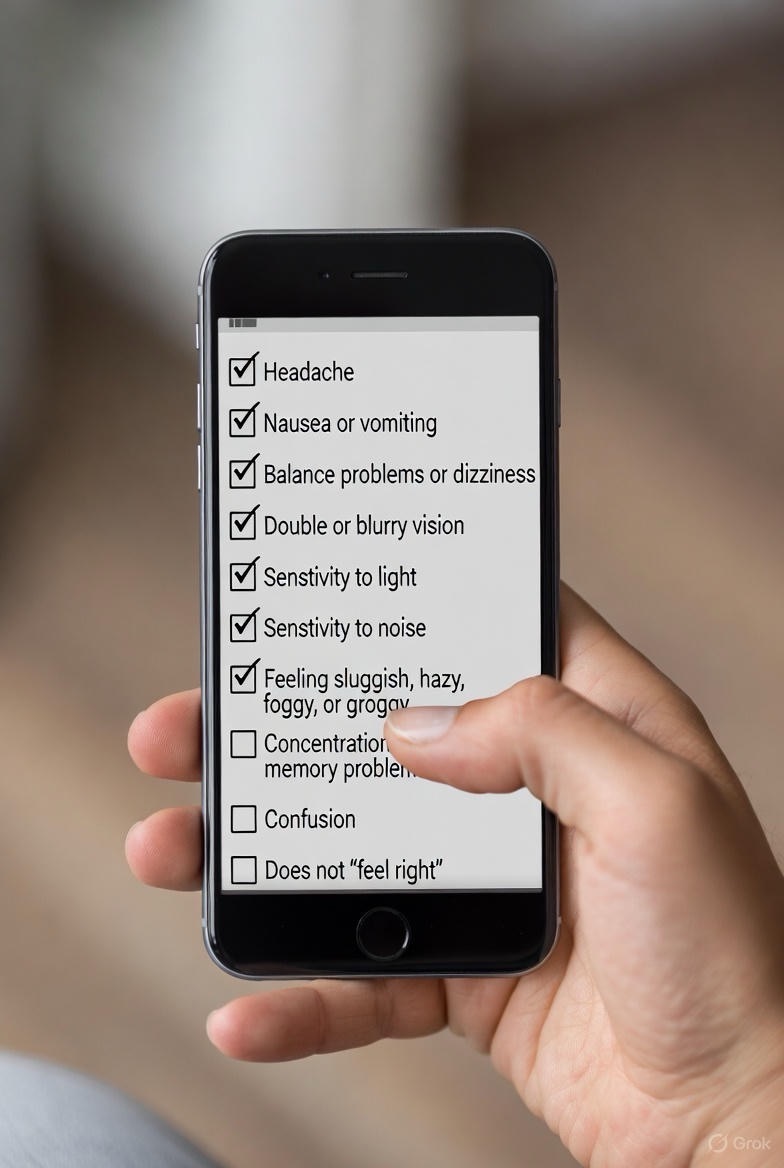

Symptoms can appear immediately or may be delayed by hours or even a day. Watch for changes in the child’s behavior, thinking, or physical state. Use the acronym “HEADS UP” as a checklist:

H – Headache or “pressure” in the head

E – Equilibrium lost (dizziness, balance problems)

A – Amnesia (can’t recall events before or after the hit)

D – Dazed or confused (appears stunned, answers slowly)

S – Sensitivity (to light or noise)

Also look for:

· Physical: Nausea or vomiting, blurred vision, fatigue, slurred speech.

· Cognitive: Feeling foggy, trouble concentrating, confusion, forgetfulness.

· Emotional: Irritability, sadness, nervousness, or unusual emotional reactions.

· Sleep: Sleeping more or less than usual, trouble falling asleep.

In very young, non-verbal children, clues are different:

· Listlessness, tiring easily

· Irritability, constant crying

· Change in eating or sleeping patterns

· Loss of interest in favorite toys

· Unsteady walking

The Immediate Response: What to Do in the First 24 Hours

1. Remove from Play/Activity: If you suspect a concussion during a sport, the rule is simple: “When in doubt, sit them out.” Do not let the child return to the game or practice. Their reaction time and judgment are impaired, making a second injury far more dangerous.

2. Seek Medical Attention: The child should be evaluated by a healthcare professional (doctor, nurse practitioner, or physician assistant) that same day to diagnose the injury and rule out anything more severe.

3. Rest is the First Medicine: Both physical and cognitive rest are crucial for the first 24-48 hours. This means no sports, rough play, or strenuous activity. It also means limiting screen time (TV, phones, video games), schoolwork, and reading, which can overtax the healing brain.

4. Monitor Closely: You will need to watch the child carefully for the next few days for any worsening symptoms.

When to Go Straight to the Emergency Room (The Danger Signs)

Call 911 or go to the nearest emergency department immediately if the child shows any of the following “Red Flag” symptoms:

· Loss of consciousness (even briefly).

· Worsening headache that will not go away.

· Repeated vomiting.

· Seizures or convulsions.

· Unequal pupil size or blurred vision that worsens.

· Significant drowsiness or cannot be awakened (check on them through the night as advised by a doctor).

· Weakness, numbness, or decreased coordination.

· Slurred speech, confusion, or unusual behavior.

· One pupil larger than the other.

· Fluid or blood draining from the nose or ears.

Trust your gut. If something seems seriously wrong, do not hesitate to seek emergency care.

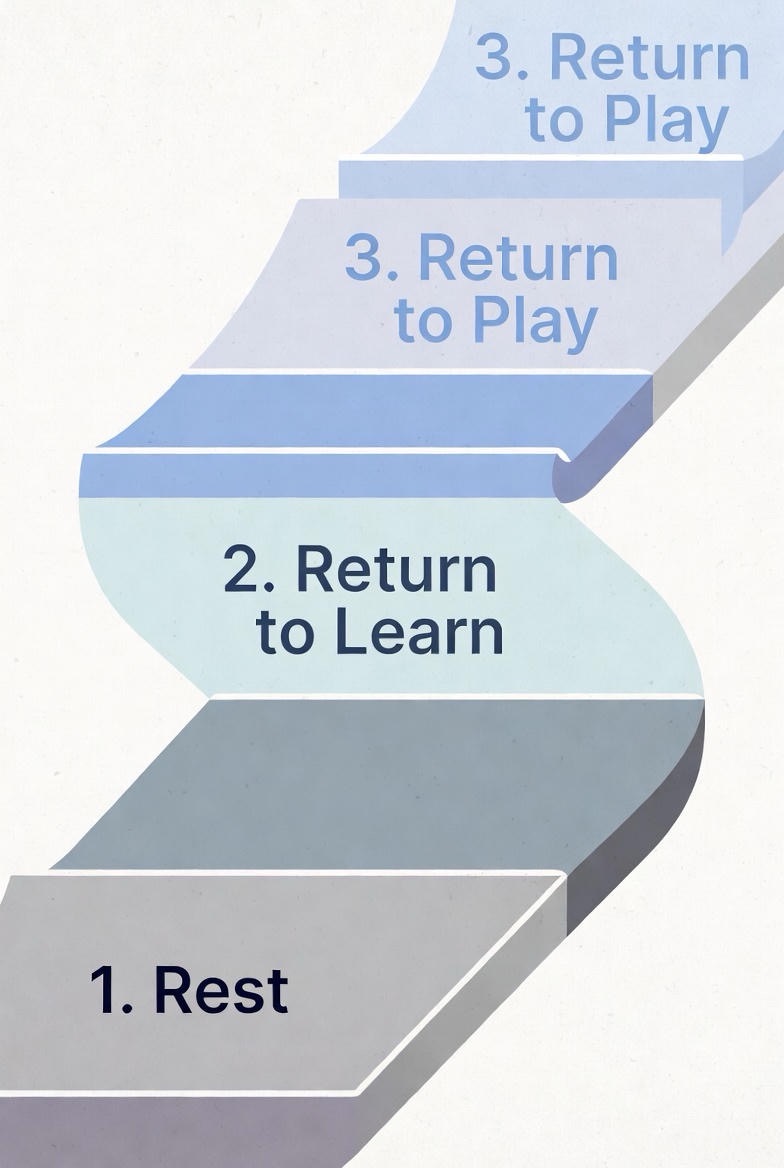

The Road to Recovery: Returning to Learn and Play

Recovery is a gradual process and is unique to each child.

· Return to Learn First: A child must be fully symptom-free during normal cognitive activity (a full school day) before even thinking about sports. This may require a phased return with academic adjustments.

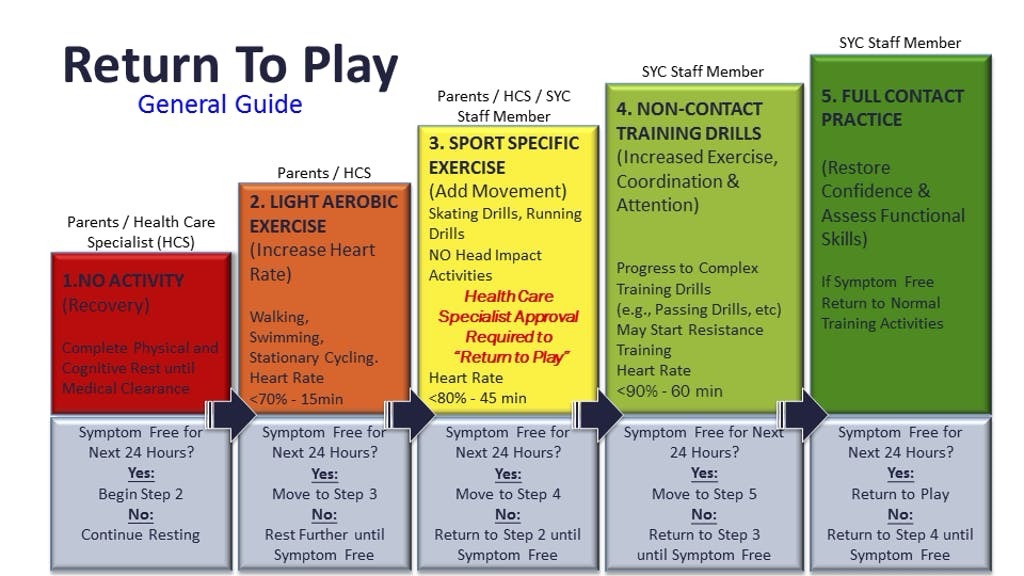

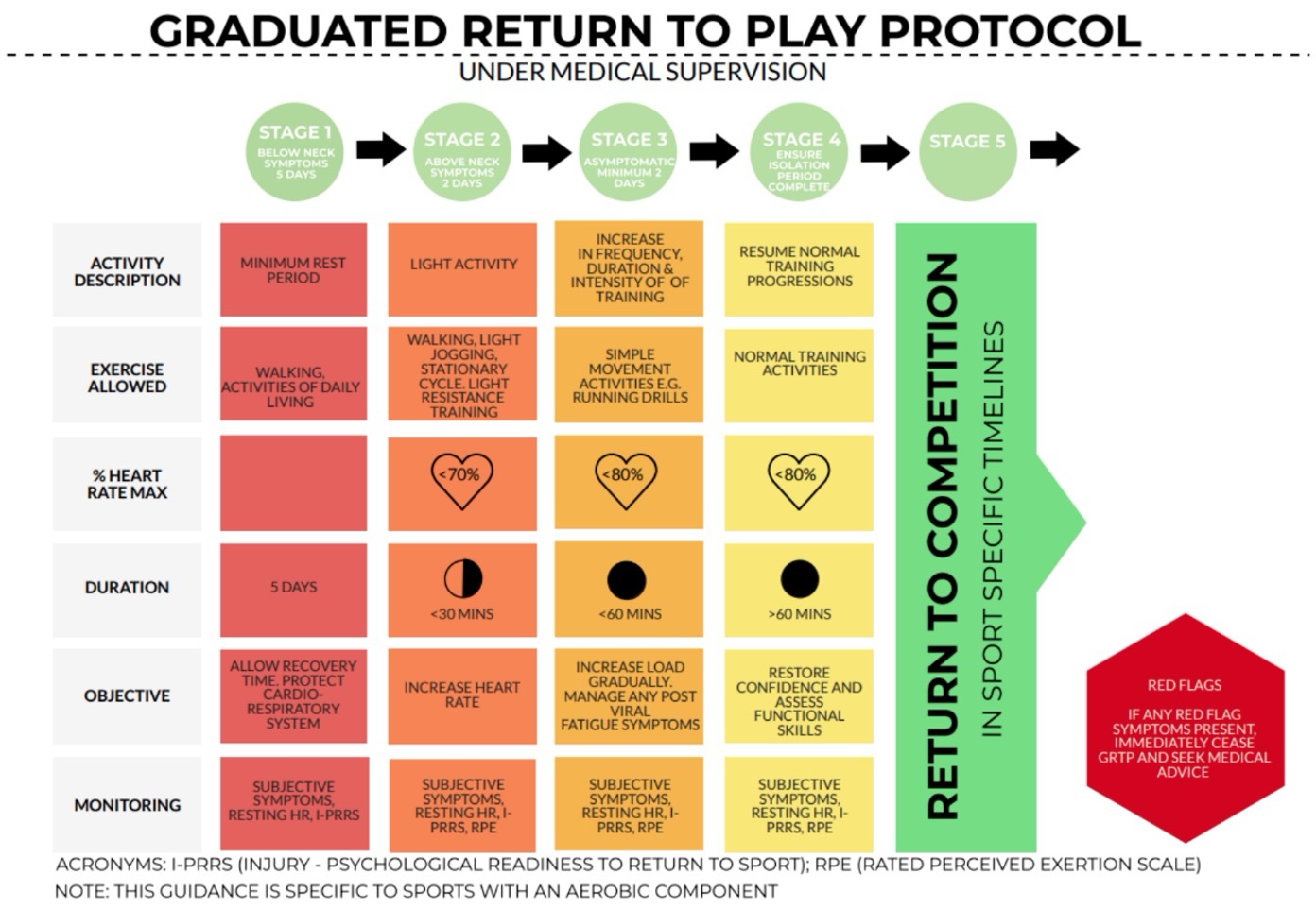

· Return to Play Second: Under a doctor’s guidance, children should follow a stepwise return-to-play protocol. This involves gradual increases in physical exertion, only progressing to the next step if no symptoms return. This process typically takes at least a week after symptoms have fully resolved.

Your Role as a Guardian

Your calm, informed response makes all the difference. You are the advocate for that child’s brain health. By recognizing the signs, erring on the side of caution, and prioritizing rest and professional evaluation, you are safeguarding their future—in the classroom, on the field, and in life.

Remember: There is no such thing as a “minor” concussion. When it comes to head injuries, it’s always better to overreact than to underreact.

FAQs

1. My child didn’t get knocked out. Could they still have a concussion?

Yes. Loss of consciousness occurs in less than 10% of concussions. The vast majority of concussions happen without the child ever being “knocked out.” Dizziness, confusion, headache, or just “not feeling right” after a hit are much more common signs.

2. What’s the most important thing to do right after a suspected concussion?

Immediately remove them from play or activity. The “When in doubt, sit them out” rule is critical. Continuing physical or cognitive exertion can worsen symptoms and prolong recovery. The next step is to have them evaluated by a healthcare professional that same day.

3. Should I wake my child up every few hours after a head injury?

For the first night, yes, this is standard advice. Follow your doctor’s specific instructions, but generally, you should gently wake them every 2-3  hours to ensure you can rouse them normally and that they can respond appropriately (know their name, where they are). This checks for worsening brain injury. After 24-48 hours, if symptoms are stable or improving, normal sleep is crucial for healing.

hours to ensure you can rouse them normally and that they can respond appropriately (know their name, where they are). This checks for worsening brain injury. After 24-48 hours, if symptoms are stable or improving, normal sleep is crucial for healing.

4. How long does it take for symptoms to show up?

Symptoms can appear immediately or may be delayed by several hours. It’s common for a child to seem fine initially, only to develop a headache, nausea, or irritability later in the day or even the next morning. Close monitoring for 24-72 hours is essential.

5. Are imaging tests like CT scans or MRIs used to diagnose a concussion?

Typically, no. A concussion is a functional injury, not a structural one like a fracture or bleed. Diagnosis is based on symptoms and a clinical exam. A doctor may order a CT scan only if they suspect a more severe injury, like a skull fracture or brain bleed (based on “red flag” symptoms), not to diagnose the concussion itself.

6. What does “cognitive rest” mean, and is screen time really that bad?

Cognitive rest means reducing activities that require intense mental focus and concentration, which can strain the healing brain and worsen symptoms like headaches. Yes, screen time (phones, tablets, video games, TV) is a major trigger. The bright, flickering lights, rapid processing, and sensory input can significantly delay recovery. Limiting screens is often the hardest but most important part of early concussion management.

7. When can my child go back to school?

This is a phased process called “Return to Learn.” They may need a modified schedule starting with half-days, breaks in the nurse’s office, extended time for tests, or reduced homework load. The goal is to increase academic activity without triggering symptoms. They must be able to handle a full school day symptom-free before returning to sports.

8. When can my child return to sports?

Only after they have successfully returned to full academics without symptoms, and under a doctor’s clearance. They must then follow a graduated “Return to Play” protocol—a stepwise increase in physical exertion (from light aerobic activity to non-contact drills to full practice). This process takes at least a week, and they must remain symptom-free at each stage. No same-day return to play.

9. Are helmets or specific headgear “concussion-proof”?

No. Helmets are vital for preventing skull fractures and catastrophic brain injuries, but they do not prevent concussions. A concussion is caused by the brain moving inside the skull, which a helmet cannot stop. Helmets are necessary protection but not a guarantee against concussion.

10. My child has had a concussion before. Are they at higher risk?

Yes. After one concussion, the brain can be more vulnerable, and the risk for a subsequent concussion is higher. Subsequent concussions can occur from less forceful impacts and may result in more severe symptoms and longer recovery times. This is why full recovery before returning to risk is so critical.

11. What are the long-term effects if a concussion isn’t managed properly?

Returning to activity before full recovery can lead to prolonged symptoms (sometimes called post-concussion syndrome), including chronic headaches, dizziness, and difficulty with memory and concentration. In rare cases, suffering a second concussion before healing from the first can cause rapid, severe brain swelling (Second Impact Syndrome), which can be fatal.

12. As a coach, what’s my legal and ethical responsibility?

You have a duty of care. Know your sport organization’s concussion protocol. If you suspect a concussion, you must immediately remove the athlete from play. Do not try to diagnose it yourself. Ensure the child is evaluated by a healthcare professional and does not return until they have written medical clearance. Ignoring this can have serious health and legal consequences.